Successful start in difficult circumstances

Planned in wartime, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Metals Research starts work in 1921. The Institute rapidly develops into an internationally renowned research institution specializing in non-ferrous metals, first in Neubabelsberg near Potsdam, then from 1923 on in Berlin-Dahlem. In 1933, the Berlin location is forced to close due to financial difficulties triggered by the global economic crisis.

Timeline

1921: Institute opens in Neubabelsberg

1923: Relocation to Berlin-Dahlem

1924: Radiography department established

1930: Physics department established

1933: Closure of Institute in Neubabelsberg

Timeline

1921: Institute opens in Neubabelsberg

1923: Relocation to Berlin-Dahlem

1924: Radiography department established

1930: Physics department established

1933: Closure of Institute in Neubabelsberg

Established in difficult times

On 5 December 1921, President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG) Adolf von Harnack comes to Neubabelsberg in person for the ceremony inaugurating the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Metals Research. The Institute is one of the first items on the wish list of the KWG, which was founded in 1911. However, no actual plans are made until World War I, which triggers a rise in demand for raw and substitute materials for use in arms production. Following the foundation of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) for Iron Research in Düsseldorf in 1917, influential industrialists and representatives of the armed forces and the KWG push for the establishment of a sister institute specializing in non-ferrous metals.

Industrialist Alfred Merton, Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Frankfurter Metallgesellschaft AG, and leading German metals researcher Emil Heyn are particularly vocal in their support for this project. On 1 November 1918, ten days before the end of World War I, the KWG proposes the establishment of a KWI for Metals Research. Industrialists have already pledged large sums of money. Frankfurt am Main offers the KWG a plot of municipal land at Merton’s instigation. Breslau also puts itself forward as a possible location. The purpose of the new Institute is to ensure that German science and industry remain internationally competitive in the field of non-ferrous metals.

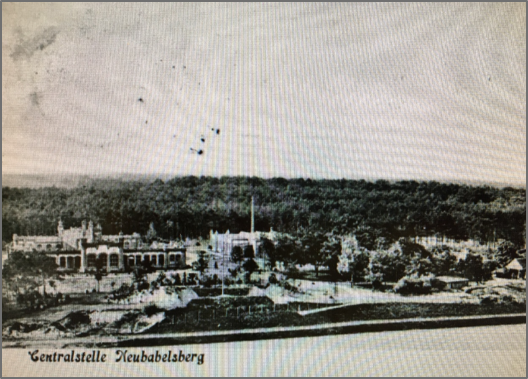

The first site in Neubabelsberg

In the end, the KWG settles for Neubabelsberg, near Potsdam; in 1920, it leases the well-equipped Centralstelle für wissenschaftlich-technische Untersuchungen (Centre for Scientific Technical Research), a research facility for the arms industry that closed after the war. On 10 June, the KWG forms a support association, passes a set of statutes, elects an administrative committee and sets up a scientific and technical advisory board. The KWG entrusts the establishment of the Institute to Emil Heyn, who on 1 July 1921 also becomes the Institute’s first Director. The KWI is built around a leading scientist in accordance with the Harnack principle.

Heyn focuses the KWI’s research on local raw materials. The goal is to compensate for the raw material and foreign currency shortages that followed Germany’s defeat in 1918. The Institute has working groups in the fields of metallography, metallurgy and analytics. Plans to establish a fourth working committee in the field of radiography do not materialize, since Heyn suddenly falls seriously ill and dies at the beginning of March 1922. His death curbs the development of the Institute, the financial basis of which is also jeopardized by inflation.

Revival in Dahlem

A move to Berlin-Dahlem in the summer of 1923 secures the continued existence of the KWI, which is temporarily housed on the premises of the Staatliches Materialsprüfungsamt (State Materials Testing Office). Its President, Wichard von Moellendorf, who was in charge of the raw materials management during World War I, also becomes the Director of the Institute. Of the three working committees, only the committee for metallography stills exists. However, a working committee for radiography is finally established in the summer of 1924 with Ernst Schiebold as its Chairman. He and his successor Georg Sachs contribute significantly to the development of radiography, a science still in its infancy which later becomes a key instrument in the field of metals research.

Beginning in 1925, Max Hansen expands the metallography division into a German research centre for two- and three-material alloys. He publishes his results in a reference work consisting of more than one thousand pages, known simply as “Hansen”. Following the appointment of Erich Schmid as the Director of the Physics Laboratory established in 1928, the Institute develops a reputation as a leading international research facility in the field of crystal plasticity. This reputation persists for several years. Even at this early stage, the Institute’s success is based on interdisciplinary cooperation.

After studying ferrous metallurgy at Bergakademie Freiberg (now Freiberg University of Mining and Technology), engineer Emil Heyn starts his career in the coal and steel industry before taking up a post in 1897 as Adolf Martens’ assistant at the Mechanisch-technische Versuchsanstalt Charlottenburg, which later becomes the Staatliche Materialprüfungsamt. In 1901, he is appointed Professor of Mechanical Technology at the Technische Hochschule Berlin (Berlin Technical College).

Together with Martens, he publishes the seminal work Handbuch der Materialienkunde für den Maschinenbau (Handbook of Materials Technology for Machine Construction). Right from the start, Heyn orients his scientific work on the practical problems faced by industry. As the first President of the Gesellschaft für Metallkunde (German Metallurgical Society), founded in 1919, and as the founding Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Metals Research, he completes the task of transforming metallurgy into a separate scientific discipline.

In crisis

Although the metal industry accounts for two-thirds of Germany’s gross domestic product in 1925, the Institute’s equipment remains modest. Even its contacts with the Reichswehr, which intends to involve the Institute in the secret arms industry, do not stabilize its situation. It becomes increasingly difficult to attract and retain renowned scientists.

Following Moellendorf’s resignation in 1929, the KWG steps up its search for a new site and sound financial backing for the Institute. The situation becomes more acute when industrial support collapses at the peak of the global economic crisis in 1932. Early in January 1933, the KWG decides to close the KWI for Metals Research in Dahlem with effect from 30 September. The lion’s share of its equipment goes to the Staatliches Materialprüfungsamt.