New beginnings under the swastika

In 1934, the Institute finds a new home and secure financial backing in Stuttgart, where it enters into a close collaboration with the Technical College. The Nazis’ autarky and armament policy dictate the researchers’ work right from the start. During World War II, the Institute is designated a research facility of vital importance to the war effort. In 1943, the Institute facilities are evacuated to various locations in Swabia in order to escape the Allied bombing raids; work continues here until the end of the war in 1945.

Timeline

1934: New start in Stuttgart

1935: Opening of the new building in Seestraße

1939: Extensions of the building occupied

1943: Evacuation of parts of the Institute

1944: Institute building in Stuttgart partly destroyed

1945: End of the war

Timeline

1934: New start in Stuttgart

1935: Opening of the new building in Seestraße

1939: Extensions of the building occupied

1943: Evacuation of parts of the Institute

1944: Institute building in Stuttgart partly destroyed

1945: End of the war

New start in Stuttgart

While searching for secure financial backing for the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) for Metals Research, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society (KWG) forges partnerships in the state of Württemberg. The internationally renowned Institute is a perfect complement to the Technische Hochschule (TH) Stuttgart and is also optimally aligned with the research interests of the local metals industry. After several years of negotiations, the parties finally come to terms on 21 January 1933, nine days before Adolf Hitler becomes Chancellor of the Reich.

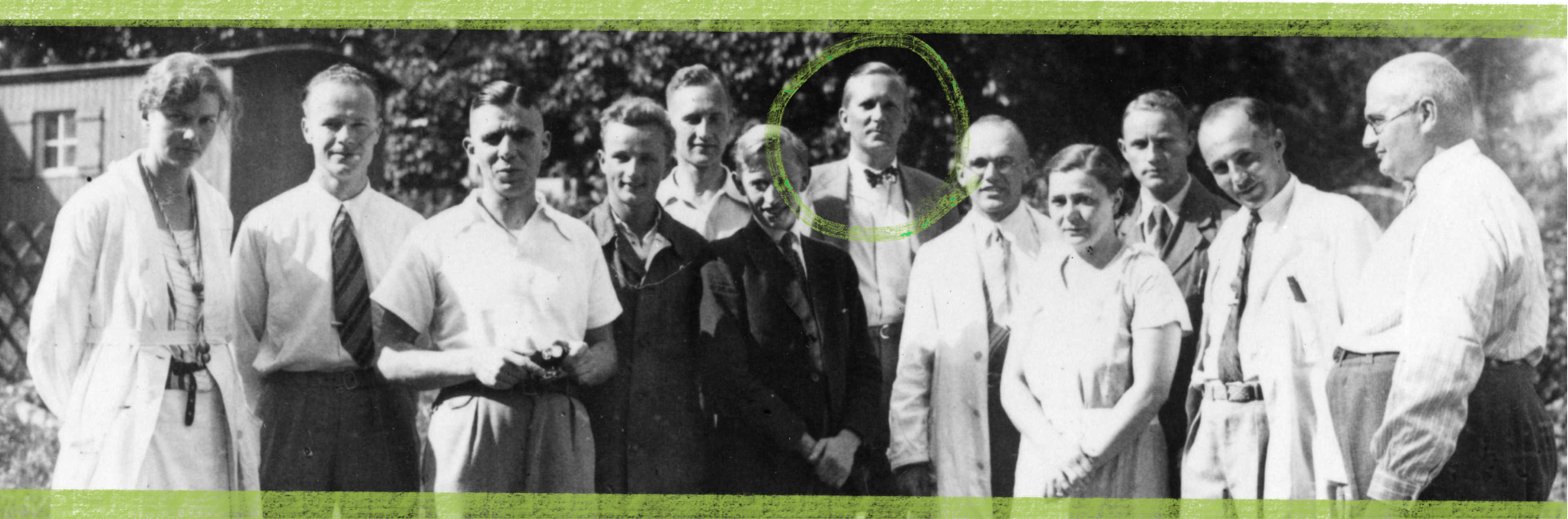

The new ruling powers bring all the scientific institutions into line within a year. The KWI’s long-time supporter Alfred Merton, who comes from a Jewish family, emigrates in 1934 due to the racist policy pursued by the Nazi regime. Georg Sachs, former Director of the x-ray laboratory and candidate for the post of Director at the new Institute, is no longer eligible because of the Nazi race laws. The young industrial scientist Werner Köster is appointed the new Managing Director and takes office on 1 July 1934. He has a decisive influence on the development of the KWI until his retirement in 1965.

A productive symbiosis

The new KWI consists of three Sub-Institutes, each directed by professors from TH Stuttgart. Werner Köster takes over the Institute for Applied Metallurgy along with a professorship at the TH. Two new Institutes emerge from existing chairs: the Institute for the Physical Chemistry of Metals directed by Georg Grube, and the Institute for X-Ray Metallurgy directed by Richard Glocker, which in 1937 is renamed the Institute for Metal Physics. The new KWI now covers all the key fields of metallurgy and presses ahead with the physicalization of metals research, a spin-off from the field of inorganic chemistry. Together with TH Stuttgart, the Institute becomes a centre for the training of research and production engineers.

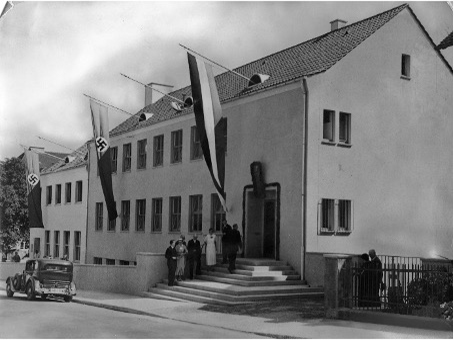

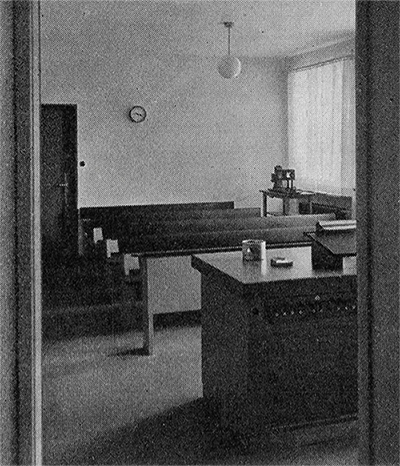

The Institute building in Seestraße

The Institute’s first dedicated building is erected in less than a year at Seestraße 75, not far from Stuttgart’s main railway station. It becomes the headquarters of Managing Director Werner Köster and the Institute for Applied Metals Research, of which he is the head. Köster’s metallurgy chair is also based here. A building extension dedicated to x-ray metallurgy links the new KWI building with the TH. The Institute for the Physical Chemistry of Metals is housed at Wiederholdstraße 13. The opening of the new building in Seestraße on 21 June 1935 is a major event attended by high-ranking representatives of the KWG, the government of Württemberg, the industrial sector and the National Socialist Party (NSDAP).

Research under the Nazi regime

The largest share of the KWI’s funding is provided by the Wirtschaftsgruppe Nichteisenmetall-Industrie (Economic Group for the Non-Ferrous Metal Industry). Its Director Otto Fitzner is a member of the circle surrounding Heinrich Himmler. The influential industrial manager and SA member dominates the KWI’s Board of Trustees, of which he becomes Chairman in 1938. Fitzner provides the Institute with substantial funding over a period of many years.

The expectations are clear: the researchers are required to support the Nazis’ autarky and armament policy.

Köster himself touts the KWI’s expertise in sectors relevant to the arms industry, one reason being to secure the Institute some of the resources that have now become so scarce. This “self-mobilization” is typical of German science during the Nazi era.

Principles and applications

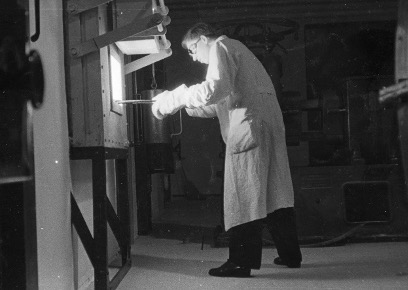

The KWI conducts intensive basic research. Werner Köster systematically measures the physical properties of metals, while his colleague Fritz Förster develops new measuring and testing processes for this purpose. Richard Glocker and his team carry out ground-breaking work in the field of x-ray research. Ulrich Dehlinger develops the concept of “uphill diffusion”. The Institute for the Physical Chemistry of Metals is the first to investigate alloy systems using thermochemical measurements.

However, the basic research carried out by the KWI cannot be strictly separated from its industrial applications. This is particularly evident from its work on alloys made of metals such as aluminium, magnesium and zinc. These metals occur in large quantities in Germany and serve as substitutes for imported raw materials. The KWI’s non-destructive materials testing processes based on x-rays and electromagnetic measurements are also used in industry. The Four-Year Plan of 1936 classifies this work as “vital to the war effort”.

Good connections

Over the next few years, Werner Köster becomes an influential science organizer. In 1936, he is appointed editor of the renowned Zeitschrift für Metallkunde (Journal of Metallurgy) and becomes a member of the Technical-Scientific Committee of the Wirtschaftsgruppe Nichteisenmetall-Industrie (Economic Group for the Non-Ferrous Metal Industry). One year later, he becomes the head of the non-ferrous metals division of the Reichforschungsrat (Reich Research Council), the central governing body for arms research in the “Third Reich”. In December 1938, Köster also takes charge of the metallurgy group of the Nationalsozialistischer Bund Deutscher Technik (National Socialist Federation of German Technology).

During the war, he also takes on other management functions in arms research organizations. In 1935, Köster’s colleague Richard Glocker becomes a member of the working group for non-destructive testing methods, which advises the Reich Aviation Ministry. The KWI is a member of the Ministry’s materials research “network”, which forges close links between science, industry and administration in order to increase efficiency.

At war

When World War II breaks out in September 1939, the KWI intensifies its arms-related research. According to Köster, the shift in focus is “particularly easy” because most of the KWI’s research projects are already classified as “vital to the war effort”.

Several alloy production and materials testing processes are already operational when war breaks out. The KWI’s research now concentrates primarily on weapon-related fields and includes new investigations into the potential of zinc as a substitute for shell detonators. The Reich Aviation Ministry becomes the KWI’s most important financial backer and client; by 1940, it is already utilizing half of the Institute’s research capacity.

The KWI’s three Directors, Köster, Glocker and Grube, join the NSDAP in 1940. In October 1941, the Institute is designated a “Luftwaffe weapons production facility”. The Institute’s status as “vital to the war effort” saves numerous staff from conscription and causes others to be recalled from the front line as the war progresses. Seven staff members who are suffering persecution on racial or political grounds are also employed by the Institute during the war.

Vital to the war effort

The KWI grows in importance during the war due to its spectacular innovations. In June 1942, Werner Köster presents an alloy of zinc and aluminium developed by his colleague Erich Gebhardt to Minister of Armaments Albert Speer at the Harnack House in Berlin. This alloy is intended to replace copper alloys in detonators, guide rings, ball bearing cages and torpedo propellers. The all-round alloy makes it possible to resume the production of ball bearings, which are vital to the war effort.

By the beginning of 1943, the KWG numbers the Institute for Metals Research among the 27 KWI doing work that could decide the outcome of the war.

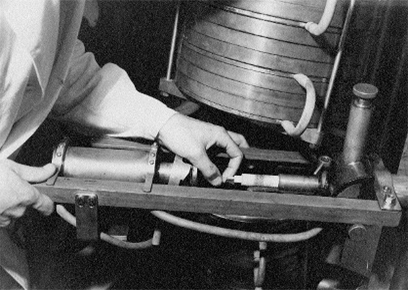

Three months later, Köster presents Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz with the “Förster-Probe”, an electromagnetic measuring device that tracks naval mines, land mines and torpedoes and can also be used to detonate torpedoes. Other flagship projects such as frostproof tank mines and pressure valves for V2 rockets secure the KWI the highest priority and with it access to additional resources. The KWI itself now becomes an arms production facility, and along with the Förster-Probe commences the serial production of materials testing equipment for the aviation industry in 1943.

Georg Sachs (1896‒1960)

Born in Moscow as the son of a merchant, Georg Sachs grows up in Königsberg, where he obtains his university matriculation qualification in 1914 before volunteering for military service. From 1918, he studies engineering at Technische Hochschule Charlottenburg, where he is awarded a doctorate in 1923 for his thesis on friction in solids. From 1924, Sachs carries out research at the KWI for Metals Research in Berlin. In 1930, he is appointed Director of the Metallgesellschaft AG research laboratory in Frankfurt am Main, and is granted a titular professorship at the university there in 1931. In 1933, Sachs, who comes from a Jewish family, becomes ineligible for the post of Director of the KWI for Metals Research due to the Nazi race laws. In 1935, he takes up the post of Research Director at Dürener Metallwerke. One year later, he emigrates to the USA. In 1938, the KWG withdraws the status of External Scientific Member awarded to Sachs in 1932; it is finally restored in 1950. Sachs initially works for U.S. industry but soon takes up posts at scientific institutions. Before his death, he holds the post of Professor of Metallurgy at Syracuse University in New York. Sachs published some 300 research papers and made pivotal contributions to modern metallurgy.

Werner Köster (1896‒1989)

Werner Köster comes from a merchant family in Hamburg. After obtaining his university entrance qualification, he volunteers for military service in August 1914. From 1919, he studies mathematics, physics and chemistry, obtaining his doctorate in 1922 with a thesis on the physical chemistry of metals supervised by renowned metallurgist Gustav Tamman. He begins his career as an assistant at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Iron Research, but in 1924 starts working in industry as a researcher. Köster is in charge of the Deutsche Edelstahlwerke laboratory in Krefeld when he is appointed Director of the KWI for Metals Research and Professor of Applied Metallurgy at TH Stuttgart in 1934. He continues working there until his retirement in 1965. Köster trains numerous metal engineers and researchers who go on to fill leading posts in science and industry. For more than three decades, he shapes the development of his field as a scientific organizer and researcher with some 340 scientific publications to his name.

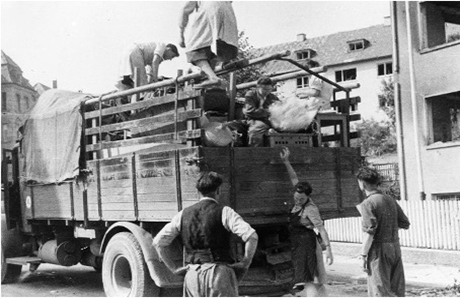

During the Allied bombing raids, Minister of Armaments Albert Speer personally supervises the evacuation of the KWI to safe locations in Swabia. In July 1943, the Institute of Metallurgy and its equipment move to Eningen, near Reutlingen, and to Urach, which also becomes home to the KWI’s central administration.

The Institute for the Physical Chemistry of Metals is housed in the Staatliche Höhere Fachschule für Edelmetalle (State Higher Technical School for the Precious Metals Industry) in Schwäbisch Gmünd, while the facilities of the Institute of Metal Physics are spread among several locations.

The evacuation does not come a minute too soon: the first bombs hit the Institute building in mid-September 1943. On 16 July 1944, the facilities in Seestraße are almost completely destroyed. The KWI continues work at its new locations until the end of the war.